The Oman Sprint

Road construction. Sand bank spilling across the shoulder. I brake hard, try to swerve and jump the curb. Wheels slip, I hit pavement. Luckily there are no vehicles passing just then or I’d be roadkill. Lucky too I hit my left knee. The right had gotten 6 stitches from my last bad fall and the doctor said there was no skin left to repair it should I crash again. I had taped both knees pre-race to support my damaged patella discs, and the tape had partially protected the knee, so what would have been a deep gash, came out in a giant lump.

Road construction. Sand bank spilling across the shoulder. I brake hard, try to swerve and jump the curb. Wheels slip, I hit pavement. Luckily there are no vehicles passing just then or I’d be roadkill. Lucky too I hit my left knee. The right had gotten 6 stitches from my last bad fall and the doctor said there was no skin left to repair it should I crash again. I had taped both knees pre-race to support my damaged patella discs, and the tape had partially protected the knee, so what would have been a deep gash, came out in a giant lump.

It is the morning of day two, and I have just passed Checkpoint 3, around 650 km into the 1,070km Oman Sprint. All my race crashes happen on day two: The World Cycle, the TransAm, the RAAM. Weird coincidence. A car pulls up and three uniformed police jump out. ‘Are you alright madam?’ They huddle around me, as I pick myself up and check that my bike, Voodoo, is okay. The left handlebar is crooked, jammed inward. I try to bang it back into place. No luck. I test the brakes, the gears. All working. Riding the last 400 with a crooked handlebar is hardly a game changer. I’ve raced on semi-broken bikes before. The police have already pulled out a first aid kit and are disinfecting my knee. The Omani people are some of the nicest I have encountered.

I thank the police and head off again, knee throbbing, each turn of the pedal more painful than the last, the bump swelling to a lemon sized lump. I don’t want to stop, but my performance is being affected, so I pull up at a little supermarket to buy ice, make a compress with my neck scarf and hold it on my knee till it has melted to almost nothing, my eyes constantly on the clock.

I had gone into this race rather ambivalently. After the Indian Pacific Wheel Race, and Mike Hall’s death, I could not find the heart or head to race again. My mind fought my legs. I thought maybe my racing days had finished with Mike. I decided to focus on riding for pleasure instead, to rediscover the joy of going on cycling adventures without the stress of a racing format. I would hit my bucket list of rides I wanted to do, starting with Patagonia. Over the Christmas and New Years’ holidays, I flew into Santiago, Chile with my partner, Vito, and we rode down through some of the most beautiful parts of Patagonia to Ushuaia, the tip of South America. I wanted to cycle somewhere in the Middle East next, as I had not passed through there on my world cycle. So when I heard about the Bikingman race in Oman, taking riders through some of the highlights of the country’s landscape, it seemed like an unmissable experience. I decided I would go into it with the view of riding it, rather than racing and see how I did. With this in mind, I did not train hard as I normally do before a big race, doing just one long 300 km ride and one 200 km with 6,000 meters of climbing.

Since I was heading there anyway, I thought it would be nice to see a bit more of that part of the world, so I flew into Dubai 4 days before the race, and cycled the 400 km to the starting line in Barka, Oman, hoping that would make for a sufficient warm up.

Anticipation was high in the lead up to the race as riders gathered over meals to discuss route, strategies, experiences and expectations. But I just wasn’t feeling it. Or rather, I was struggling to supress the first stirrings of a now familiar dread. I sat in my hotel room and meditated. It’s just a ride. I kept repeating to myself. You love riding your bike, so go have fun and do what you love.

As the racers gathered for the 3:00 am start, I rolled up to the back of the group, wished luck to other women who I knew were all nerves at this, their first ultra-race. People are generally wound tight as a guitar string at the starting line and the first few hours of the race is something like a mad peloton sprint till riders begin to mellow and spread out along the route. I’ve done enough of these races to know you have got to pace to race, so I settled into my handlebars at a sustainable speed, conserving my energy for the first big challenge towering at the 330 km mark: Jebel Shams.

Forty kilometres in, the gradients began to gradually increase and as the sun rose, the landscape unveiled itself in all its incredible beauty. The road wound and rolled through mountainous terrain, surrounded by colourful rock formations on all sides. With daylight too, came strong winds that grew steadily stronger over the course of the day. The race projection showed an average -1% gradient for a long 50-kilometer stretch leading up to the big climb, Jebel Shams. Great! A bit of active recovery before monster mountain, I thought. Rarely does theory ever match reality in these kinds of races. By that point, the headwind was so strong, I was pushing hard at 20 kmph on the downhill. So demoralizing was this wind, that I made my first service station stop at 250 km, even though I had not intended to stop till I reached CP1 at 350 km, the top of the climb. There’s nothing like coconut water and a lot of icecream to boost morale. Spirits slightly revived, I carried on, arriving at the foot of the climb at around 5:00 pm, a couple hours behind my projected time.

Forty kilometres in, the gradients began to gradually increase and as the sun rose, the landscape unveiled itself in all its incredible beauty. The road wound and rolled through mountainous terrain, surrounded by colourful rock formations on all sides. With daylight too, came strong winds that grew steadily stronger over the course of the day. The race projection showed an average -1% gradient for a long 50-kilometer stretch leading up to the big climb, Jebel Shams. Great! A bit of active recovery before monster mountain, I thought. Rarely does theory ever match reality in these kinds of races. By that point, the headwind was so strong, I was pushing hard at 20 kmph on the downhill. So demoralizing was this wind, that I made my first service station stop at 250 km, even though I had not intended to stop till I reached CP1 at 350 km, the top of the climb. There’s nothing like coconut water and a lot of icecream to boost morale. Spirits slightly revived, I carried on, arriving at the foot of the climb at around 5:00 pm, a couple hours behind my projected time.

I’ve climbed a lot of mountains, so many I’ve lost count. I like climbing. I look for challenging ascents wherever they may be. I find my rhythm, settle into it, my breathing levels out and I scale the thing no matter how long it takes or how steep. But nothing could have prepared me for this one. Nothing, in all my cycling experience, could hold a dim candle to Jebel Shams. When the organisers called it “mayhem”, I thought, cool. I mean it’s only 20km, how hard could it possibly be? Oh what a naïve and foolish girl I was.

While the extreme freeze across Europe was being referred to as the “beast from the East”, I was riding up its literal definition. Well, half riding, half walking. The fact that my fingers and toes kept cramping from salt loss was a serious impediment to progress. At one point, I took off my cycling shoes and went barefoot as it was the only way to keep my toes from seizing up. It would be brutal with fresh legs, after 330 km it was downright torturous.

While the extreme freeze across Europe was being referred to as the “beast from the East”, I was riding up its literal definition. Well, half riding, half walking. The fact that my fingers and toes kept cramping from salt loss was a serious impediment to progress. At one point, I took off my cycling shoes and went barefoot as it was the only way to keep my toes from seizing up. It would be brutal with fresh legs, after 330 km it was downright torturous.

The sun sets early in Oman. I hit the 8 km gravel section halfway up the climb just as daylight faded and it was only then that I discovered to my dismay, that my front light connected to the dynamo did not seem to be working. I had a cheap back up that threw only the faintest glimmer on the road ahead. I nearly slipped off the edge on a couple sections and opted for a slow crawl when pedalling, walking the really bad bits. Better safe than sorry. I was also completely depleted of energy and out of water. But the night was fresh and peaceful, the silence under the stars a pleasant break from the stress of the race. I found one of the riders, Robbie, on the road and we huffed along side by side for a few kilometres remarking on how surprisingly pleasant this bit of suffering was just now. All the same, the glittering lights of the Jebel Shams Resort, the checkpoint at the top, were a welcome sight.

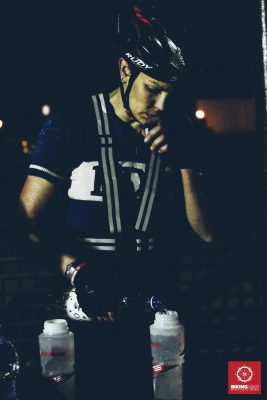

They had a giant buffet waiting for hungry riders. This was my first proper meal since the race started, and while I was hungry, it was difficult to put down much food. I tanked up on liquids, refilled my water bottles, slathered on fresh diaper cream and went out to try and fix my light before the harrowing descent in the dark. It seemed one of the internal wires was loose, a problem that had me questioning my ability to continue through the night. Providence stepped in when one of the riders who had scratched passed off his batteries and spare headlight. I now had two good lights to get me through the night. My legs felt heavy, but in fairly good shape considering the amount of climbing and mileage they had covered till now. By the time I got down the mountain, the wind had died, the temperature was fresh, I was perking up.

They had a giant buffet waiting for hungry riders. This was my first proper meal since the race started, and while I was hungry, it was difficult to put down much food. I tanked up on liquids, refilled my water bottles, slathered on fresh diaper cream and went out to try and fix my light before the harrowing descent in the dark. It seemed one of the internal wires was loose, a problem that had me questioning my ability to continue through the night. Providence stepped in when one of the riders who had scratched passed off his batteries and spare headlight. I now had two good lights to get me through the night. My legs felt heavy, but in fairly good shape considering the amount of climbing and mileage they had covered till now. By the time I got down the mountain, the wind had died, the temperature was fresh, I was perking up.

I love night riding. I go into a place of internal observation, my body in auto mode, my thoughts in a kind of waking dream space. I lose time that way, hours can go by without noticing. By the time the morning sky began to lighten from purple to lavender, I was closing on Ibra and checkpoint 3. I stopped for coffee and eggs at a little Indian-run roadside café. It was at least another 50 km to the CP and I couldn’t wait that long for food. A whatsapp voice message came through from race director Andreas as I got rolling again. Hurry up, he said. Racers Paul and Josh Ibbett had just gotten to the checkpoint, I was only an hour behind them and closing in at 7th position. This was a surprise. I had determined not to watch the other riders’ dots during the race, because I had not intended to race it, wanting to just enjoy the ride without thinking about my place in it. But now…well, this changed things. I stepped on it.

Josh had just finished breakfast and Paul just left as I rolled up to the control. I sat down for a second breakfast, stuffing down a plateful of rice and an omelette, more coffee, refilled my bottles, and went through the usual self-care routine. “Have you slept?” Josh asked me before he left.

I had not. This, in fact, was what now powered me forward. Once I’d discovered my race legs and headspace during the night, I made a decision. Every race I do is to test myself, my abilities and challenge what I know to be true. Until now, the furthest I had ever ridden non-stop was 800 km in the final 36-hour stretch to the finish line of the Trans Am Bike Race. I wanted to break that personal record and do 1,000 km non-stop and I wanted to do it in 48 hours. I was 630 km in, with a little over 400 to go. It was around 10:00 am. I could do this. Time to get moving.

With two breakfasts worth of energy, I took off racing into the desert, then…skid, slip, crash. Stupid, stupid, stupid.

Knee iced, I am eager to make up the lost time. The sun has fully risen and the heat rising off the desert sand is scorching. My black shoes are like a furnace, my toes inside roasting and blistering. I stop again, tear off my shoes and socks and wrap my toes in bandages to relieve some of the tenderness. This next part, I know, is going to hurt. With the sun, the wind too starts to pick up again and as I hit the coast heading towards Muscat, the gusts turn more violent but since it’s mostly flat, I manage to sustain a steady momentum.

Somewhere along this seemingly never-ending road, I pick up news that the guy who was leading the race was caught cheating with a support vehicle. I wonder what’s the point? This is not a race of professionals being paid to win. There is no prize at the end other than backslaps and cold beer. This is a bunch of crazies on a mad adventure for the hell of it. But perhaps more importantly, it is a community of like-minded people who ride for the love of riding and for the purity of the sport. And once your name is blacklisted in that community, you will never be able to sign onto another race. Ever. He has just destroyed his foreseeable future of unsupported ultra-racing…for what?

The race elevation projection shows mostly flat till the 850 km mark, which then turns into a series of rollers which, on my app, look very much like jagged teeth. What then is my surprise to hit a series of sharp, steep hills going into the city of Sur at least 50 km earlier than projected. Apparently, the longest and steepest of these is called Tiger mountain by the locals, because, well, the rock leading up the climb is painted into a giant tiger. Why. There are no tigers in Oman. Just. Why. buy generic Ivermectin Fuck you tiger. You and your tiger climb. The thought briefly flashes through my mind to put Eye of the Tiger on my current playlist, because that opening rift would definitely crack me up and I could use the humour, but I am too tired to take my hands off the steering and I’d rather not slow my already slow pace with the effort.

The race elevation projection shows mostly flat till the 850 km mark, which then turns into a series of rollers which, on my app, look very much like jagged teeth. What then is my surprise to hit a series of sharp, steep hills going into the city of Sur at least 50 km earlier than projected. Apparently, the longest and steepest of these is called Tiger mountain by the locals, because, well, the rock leading up the climb is painted into a giant tiger. Why. There are no tigers in Oman. Just. Why. buy generic Ivermectin Fuck you tiger. You and your tiger climb. The thought briefly flashes through my mind to put Eye of the Tiger on my current playlist, because that opening rift would definitely crack me up and I could use the humour, but I am too tired to take my hands off the steering and I’d rather not slow my already slow pace with the effort.

Another message from Andreas tells me Josh has just gotten into Sur and the other two in front are only an hour or two ahead of him.

I stop at Sur for my final food and water refill. I won’t stop again till the finish. The rest of the route will include at least 2500 meters of climbing all the way to the end. My legs have reached the point where the pain and exhaustion have levelled out into a kind of constant dull ache, easily ignorable. To my delight, my knees have held up the whole way. The last couple races, they got bad enough to cause serious issues, and since I am allergic to anti-inflammatories, once they go, that’s it, game over.

A lot of speed bumps and traffic passing through Sur makes it difficult to pick up momentum, but once out on the open highway, I find my pace again. Less than 200 km to go, you got this. Vito calls. “You’re doing great, babe! Looks like the guy who was in front of you and Josh has dropped behind you. You’re in fourth position now.”

This barely registers, or I am past caring. Second night with no sleep and I am starting to feel the toll. I just want to get to that finish. The hills come one after another and feel never ending, but the gradient of the longest 10 km climb is still milder than I had anticipated. Or maybe after Jebel Shams, everything feels easier. The wind has died, the night air is cool, the road smooth and well lit, the traffic sparse. I can smell the finish. I put on an audiobook to get me through the last hours, settle into the aerobars and push. The hours tick by in a kind of hallucinatory haze. Road signs, light posts, even parked vehicles and shadows morph into people that move and turn to look at me as I pass. This keeps things interesting, amusing even. Who needs drugs? Go ride an ultra if you want to trip.

Sometime after 1:30 am, I get a photo through whatsapp from Andreas. The first rider, Rodney, a tough Peruvian who knows mountains, has arrived into the finish. Oh to be him right now. So close still feels so far. A voice message from Andreas says there may be a problem with the given route on the last section coming into Muscat. “Take the alternative on the highway.” I don’t understand much at this point, all instructions seem complicated. “Just stay on the highway you’re on. Ride it all the way into the city. It’s a bit longer, but the road is good.” He instructs. Roger. Stay on the highway. I can do that.

At around 2:30am, I pass 1,000 kilometers. I have ridden 1,000 kilometers non-stop and unsupported in under 48 hours. I pump my fist. Yes! My new personal best. My adrenaline gets a little surge. Let’s get to that finish in under 50. Ride, woman! There’s a bed at the end. With everything I have got left in my legs, I sprint.

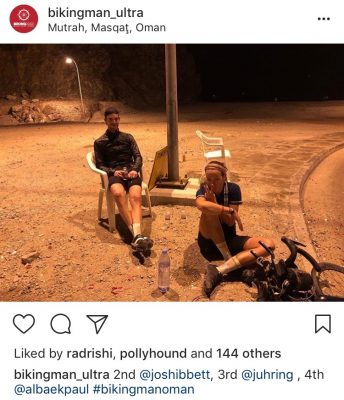

Vito calls every half hour, to be sure I stay awake. Past the two-day mark on no sleep starts to get dangerous. I feel my legs pumping mechanically, but my brain is beginning to fog. The last hour to the finish, I register almost nothing. I roll around aimlessly looking for the finish line, stopping someone at a crossing to ask for directions to the lighthouse. I find the giant egg cup looming in front of me, but I can’t find the entrance to the finish. Vito stays on the phone with me, since I am almost incoherent. Then I see a little entrance to a beach cove where a vehicle is parked. Someone is sitting in a chair. Is that the finish? I roll down to find Josh Ibbett slumped back in a white plastic chair. “Heeey, you made it. Congratulations.” He says. “Congrats to you. Great ride man.” I put out a hand and he shakes it. Only then do I notice Rodney crashed out in a sleeping bag on the sand next to the race vehicle. “You’re in third place.” Andreas says coming over to put the final stamp in my brevet card. 1,070 km in 49 hours, 53 minutes.

Vito calls every half hour, to be sure I stay awake. Past the two-day mark on no sleep starts to get dangerous. I feel my legs pumping mechanically, but my brain is beginning to fog. The last hour to the finish, I register almost nothing. I roll around aimlessly looking for the finish line, stopping someone at a crossing to ask for directions to the lighthouse. I find the giant egg cup looming in front of me, but I can’t find the entrance to the finish. Vito stays on the phone with me, since I am almost incoherent. Then I see a little entrance to a beach cove where a vehicle is parked. Someone is sitting in a chair. Is that the finish? I roll down to find Josh Ibbett slumped back in a white plastic chair. “Heeey, you made it. Congratulations.” He says. “Congrats to you. Great ride man.” I put out a hand and he shakes it. Only then do I notice Rodney crashed out in a sleeping bag on the sand next to the race vehicle. “You’re in third place.” Andreas says coming over to put the final stamp in my brevet card. 1,070 km in 49 hours, 53 minutes.

“What? I am? I thought you were in third place.” I say to Josh.

“Nope, the other rider, Paul, never turned up.”

“Babe, I’m third.” I say to Vito, still in my ear set.

“Wow baby, congratulatioooooons! Brava!” He roars and I think I’m smiling, but I can’t be sure what I feel just now except relief and, oh yes, I can finally get off my bike. I dismount, lay a battered Voodoo on the tarmac, and crumple, joints creaking, onto the sand next to Josh. Ouch. Bum hurts. Everything hurts. We just sit there, staring, dazed, and I think we talk, but I remember nothing except a kind of surprise it is over. Maybe this is what shell shock feels like. An hour passes in this semi-stupor. A shower and a bed would really hit the spot, I think.

“Is there somewhere we can sleep?” I say.

“There’s a hotel a few kilometres away. I’ll get a taxi to take you both.” Says Andreas.

“Maybe they’ll serve breakfast by now.” Says Josh.

All I have eaten in the last eight hours was a handful of nuts. “Yeah. Breakfast would be good.” Then shower. Then sleep. In that order.

ian guignet

March 7, 2018 @ 13:33

Amazing as always! Brilliant update Ju. Good to see you crushing it via dot watching. Congratulations!

Mike Kelly

March 7, 2018 @ 13:59

again you are inspiring me to do a 5 day ride supporting the MS Society. (70 years)

David Otte

March 7, 2018 @ 15:13

70 years? I hope I make that. You are an inspiration as well.

David Otte

March 7, 2018 @ 15:10

Beautiful writing, excellent endurance ! Thanks very much for the read and continuing inspiration!

Kevin Longworth

March 7, 2018 @ 15:20

Such an inspiration to all of us who complain about minor things as if they were a hardship. No more whining, carry on! You are truly an inspiration.

Corrine

March 7, 2018 @ 16:03

Great write up. Great race! Thanks for sharing. Funny how the competitive edge creeps in even when we think it won’t!

Shayla Pfaffe

March 7, 2018 @ 17:04

Loved the writing and you are one incredible woman! Simply unbelieveable!

Amy

March 7, 2018 @ 17:20

Brilliant. Riding. Writing. Passion.

I so enjoy following your journeys, thanks for sharing

Annalisa

March 7, 2018 @ 19:12

An inspiration as always!!!

Michael Aranguren

March 7, 2018 @ 21:10

Yes you are the toughest woman in sports, keep it up Juliana incredible writing kept me on my toes the whole time wow amazing

Simoni

March 7, 2018 @ 23:00

Campeona! The way you ride, the way you tackle the hard stuff, they way you set new goals. This is what riding is about at the core of it. I don’t know of any other riders like you. Settling into the pace, into the RYTHM, with the kilometers, the hours just passing by. Love that. And you got nothing to prove to anyone except yourself. Great writing as always. There’s a saying: when an old horse of the circus returns and smells the sawdust, it awakens the spirits of the past, the adrinaline rushes in the veins again at the entrance to the arena, ready for another stellar performance. 🙂 You still know how to do this when it counts. Like a true champion. Brilliant stuff.

Mário Fonseca

March 8, 2018 @ 10:20

Thank you so much for sharing this.

We can do such amazing things when we love what we’re doing.

Any ultra is a mix of pleasure and – I don’t want to say “hate” or self-loathing – pain. We’re the ones harming ourselves and I can’t point out the reason why.

Riding until all that’s left is a life-supporting auto pilot gets us to that place where nothing else matters, only surviving… or win a race, or our own race.

If only that drive worked for everything in our lives…

Thank you

David Stihler

March 9, 2018 @ 02:33

Such an inspiration for me and everyone who knows you. These are not just words, I feel so enlightened and empowered reading about your journey and challenges. Keep communicating, keep riding!!!

Bataille

March 10, 2018 @ 15:57

Always a big pleasure to read tour aventures ! You make my Day 😅

Dave Ashenfelter

March 13, 2018 @ 09:34

You ROCK!!

Bob Hansler

March 15, 2018 @ 16:03

This young lady is a true inspiration to us all (Yes, including us old folks). The best of love goes from Swansea to you and all those who love you.

radioprima

March 16, 2018 @ 19:49

Thank you, Marette!

Kieran

March 23, 2018 @ 12:53

Awesome, you are really the best great write up love hearing your perspective, sham on that rider for using the support vehicle!